The greater majority of athletes have experienced a sprained ankle at some point in their career. After all, sprained ankles are the most commonly injured joint in athletes accounting for approximately 34% of all injuries and 80% of all injuries in soccer players according to a 2007 study in Sports Medicine.

The problem with lateral ankle sprains is not limited to the initial injury. In fact, it is the vicious cycle of spraining it again and again and AGAIN that victimizes athletes. Chronic Ankle Instability or tendency toward repeated ankle sprains and recurring symptoms such as poor postural control, decreased joint awareness, and joint instability are estimated in up to 80% of athletes who have experienced a prior ankle sprain. This article will discuss what really happens when you sprain your ankle, the proper treatment to stop the cycle of repetitive injury, and how to determine when you are ready to return to play.

Please note the information provided in this piece is NOT meant to diagnose or treat specific individuals. If you have a sports medicine injury or illness you need to consult with an appropriate medical professional.

LATERAL ANKLE SPRAIN: WHAT IS IT AND WHAT HAPPENS?

Mechanism of Injury: Most lateral ankle sprains occur from a rolling inward movement that causes excessive inversion (moving sole of foot toward body) and plantar flexion (toes pointing partially downward). This is often seen with landing on someone’s foot, cutting/changing directions, and poor field conditions. Or in the case of Lady Gaga….wearing shoes that put your ankles in excessive plantar flexed positions. No wonder she can’t stop falling down…

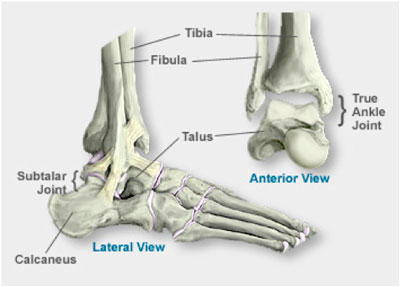

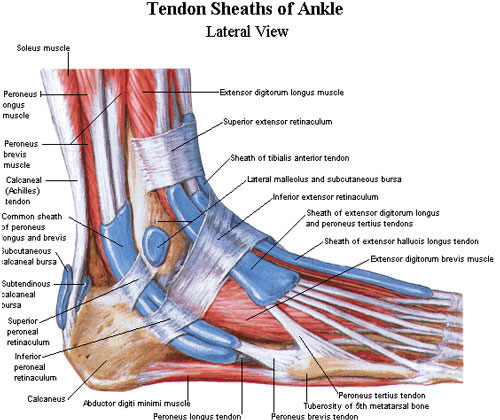

The ankle and foot complex is composed of 28 bones, 31 muscles, and 25 joint complexes.

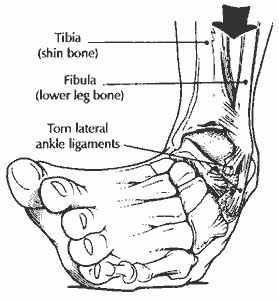

Bones most specific to a lateral (meaning outside or away from center of body) ankle sprain include those that help form the talocrural joint or ankle mortise: tibia (shin bone), fibula (outer leg bone), talus (bone that sits on top of your heel bone). In addition, one major ligament involved in these sprains also attaches to the calcaneus (heel bone).

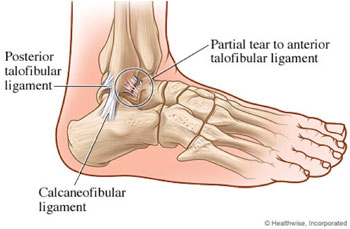

Ligaments (which connect bone to bone) specific to lateral ankle sprain include: anterior talofibular ligament (ATF), calcaneofibular ligament (CF), and posterior talofibular ligament (PTF). These 3 ligaments along with the deltoid ligament on the medial (inside) aspect of the ankle work to keep the two lower leg bones together to a form a mortise with the talus bone underneath, providing your ankle with both stability and mobility. The ATF is the most commonly injured ligament in a lateral sprain followed by the CF and rarely the PTF. Most ankle sprains involved 1-2 ligaments and rarely all 3.Ligaments that are injured not only become more lax but will also have compromised ability to sense where the joint is in space, how fast it is moving, and forces applied to it. This is a main reason why athletes have recurrent injuries. They rush back into battle without all of its defense systems functioning appropriately.

Muscles most often compromised include the fibularis longus and fibularis brevis (also known as peroneals). These muscles allow you to evert (turns sole of foot outward) and often become strained or overstretched when the ankle is rolled inward. As a result, their ability to produce timely and appropriate muscle contraction is compromised and must be relearned.

PROPER TREATMENT:

An athlete should see a sports medicine physician to rule out a possible fracture if any of the following:

– Presence of an obvious deformity (ie. broken bone, dislocation)

– Inability to bear weight on affected extremity for four steps

– Tenderness along the bone directly ABOVE the medial or lateral malleoli (your “ankle bones”)

Grades of Sprains: Grades are determined by the amount of damage to the ligament(s).

Grade 1: Overstretching of ligament – microscopic damage, minimal impairment, minimal tenderness and swelling.

Grade 2: Partial tearing of ligament, moderate impairment, moderate tenderness and swelling/decreased range of motion/possible instability.

Grade 3: Complete tear of ligament, severe impairment, significant tenderness and swelling/definite instability.

Immediate Treatment for a sprain commonly includes Protection, Rest, Ice, Compression, and Elevation (PRICE) to manage acute symptoms/pain. Research (Green et al, 2001) also supports the benefit of early gentle anterior-posterior joint mobilization by a physical therapist trained in manual therapy to speed up recovery time. Gentle muscle setting (isometric) exercises are recommended at this time as well to maintain muscle integrity.

Turning Traditional Thoughts on Swelling Upside-Down:Food for thought…this 2010 study demonstrates the positive effects of swelling on muscle regeneration. If swelling is a natural protective and regenerative response of the body why would we want to stop it? Now, I’m not advocating everyone let their ankles blow up to the size of balloons just yet. Excessive swelling does contribute to pain as well as muscle inhibition and also restricts full range of motion. However, some swelling in the early stages of an injury may be OK and consider ditching the use of anti-inflammatory medications like ibuprofen (Advil) and use acetaminophen (Tylenol) for pain instead. Steering clear of ibuprofen is a common practice in the management of stress fractures to help promote healing and your GI tract will thank you as well. Stay away from the cortisone shots while you are at it too! A summary of the 2010 study that doesn’t require a biochemistry degree can be found here.

Sub-Acute Treatment: Once an athlete can bear weight and initial symptoms are subsiding, the following steps should be taken under the guidance of a physical therapist.

-Use of splint/brace – generally recommended for Grade 2 or higher to preserve ligament integrity at end range motions to allow healing during active recovery. Grade 3 injuries are most often immobilized in a walking boot or cast at which time the following steps will be delayed.

-Active Range of Motion (ROM) work – such as writing the alphabet with toes

-Kinesthesia – specific exercises for retraining recognition of joint motion.

-Muscle Strengthening – include all muscles groups acting on ankle complex along with intrinsic foot muscles. Special attention should be dedicated to ankle evertors (fibularis longus and brevis).

-Cross Friction Massage to ligaments involved and progressing with joint mobilizations – helps collagen fibers in ligaments align in a manner that allows strength and appropriate mobility and prevent adhesions.

– Pool or Bike Workouts as tolerated to maintain cardiovascular fitness

Return to Function: Once athlete has full ROM, full weight bearing, and absence of swelling the following activities should be incorporated into daily rehab.

– Neuromuscular Training – Balance and proprioceptive training progressing from both static to dynamic and stable to unstable surfaces

– Progress with strengthening exercises by adding resistance

– Progression to plyometric activities – begin with two-leg (jumping) and progress to single-leg (hopping); progress to adding distraction component with cognitive task

– Eventual progression to running and cutting activities – begin with linear running progressing gradually to 90 degree cuts at full speed. Final progression is top speed agility in unpredictable environments.

RETURN TO SPORT When is an athlete ready to play? An athlete must demonstrate the following.

– Full Range of Motion– special attention needed for restricted dorsiflexion which is often caused by tight calf muscles and to a greater extent, the anterior migration of the talus in the ankle mortise.

– Pain Free Movement – the athlete must be able to reproduce ALL movements required by their sport.

– Absence of Swelling

– Absence of Instability – the athlete should not be experiencing episodes of the ankle “giving out”. The more the unstable the joint, the more bones crash into one another resulting in arthritis in the future and poor performance at present.

– Full Dynamic Balance – the standard accepted measure is a 94% composite score adjusted for leg length on the Star Excursion Balance Test. Female athletes have a 6.5 times greater chance of lower extremity injury with a score of less than 94% according to a 2010 study in the Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy.

– Symmetry in Functional Measures – standard accepted measures are 90% symmetry or greater with unaffected side in selected objective measures such as 6m Crossover Hop, Figure 8 Hop Side Hop, and similar measures.

Bracing vs Taping? Which one is better?

Ideally I want an athlete’s body functioning properly so they don’t have to rely on a “crutch” such as taping or bracing. In addition, I am not a big fan of restricting ankle motion for the simple fact that a person needs a baseline amount of ankle motion or the body will find it somewhere else (read compensations….read injuries at another joint.) External supports only address the symptom (instability) and not the cause (poor neuromuscular control, poor strength). Not to mention they just feel unnatural in soccer shoes. However, ankle bracing and taping are appropriate for short term protection of the joint while an athlete is returning to play and have both been proven to offer some joint stability and increased proprioception to reduce future injury. Semi-rigid braces with a subtalar locking system tend to perform the best in studies. Lace up braces and ankle taping offer some benefit in terms of increased muscle activation with some motion restriction versus no support at all. Kinesiotape (the stretchy black tape you often see in the Olympics) offers no significant benefit in terms of support or muscle activation specific to the ankle.

With that in mind, a brace in poor condition or poor fitting well may be less effective than a proper ankle taping. It’s all relative and there is something to be said about the positive effects of the placebo effect. Bottom line: In my opinion, a good neuromuscular training program is the body’s first and best line of defense against ankle sprains. The body must learn to protect itself. Bracing/taping can both provide additional benefits in both ankle sprain prevention and in return from an injury but be careful of making the body completely reliant on external support. If you are going to wear a brace long term, make sure you also on a good ankle prehab/rehab program as well.

STOPPING THE ANKLE SPRAIN CYCLE:

1. Stop the first injury: Train the body to protect itself with an appropriate strength and conditioning program or dynamic warm-up that incorporates elements of balance and neuromuscular training. Part of my U18 team’s warm-up includes jumping and hopping as well as volleys while hopping on one leg. We get in about 1620 hours of injury prevention work this year via our daily warm-up and had no major knee injuries, just 1 new ankle sprain, and 1 minor hamstring injury in total for the year.

2. Don’t rush back from an ankle injury: The #1 reason individuals have recurrent ankle injuries is because they rush back to play once the pain and swelling are gone, but completely ignore the range of motion, strengthening, and neuromuscular control pieces.After a ligament injury, bones can shift preventing full range of motion and the body loses its ability to defend itself unless relearned. Don’t throw it back on the proverbial race track until you have the car working properly on all fronts or you will end up crashing into the wall again. Chronic ankle sprains that go untreated lead to early arthritis, compensations by neighboring joints, and long term joint laxity….and more injuries.

A WORD ABOUT SURGERY

Primary lateral ankle ligament injuries including Grade 3 sprains are usually managed very effectively without surgical intervention with appropriate physical therapy. Speak to your orthopedist about the appropriateness of surgical intervention if conservative measures have proven to be ineffective in managing symptoms.

About the Author: Julie Eibensteiner PT, DPT, CSCS is a physical therapist and owner of Laurus Athletic Rehab and Performance LLC, an independently owned practice specializing in ACL rehab and prevention in competitive athletes. In addition to being a regular contributor to IMS on topics of sport injury and prevention, Eibensteiner holds a USSF A License, coaches a U18G MRL team for Eden Prairie Soccer Club, and assists with the Men’s and Women’s soccer programs at Macalester College.

Clap

Clap